On phones, “contacts” refers to your device’s address book (names, phone numbers, emails, notes, birthdays, etc.). Granting access lets an app read some or all of those fields; some apps may also request the ability to create/update contacts.

- Android. Apps declare specific dangerous permissions such as

READ_CONTACTSandWRITE_CONTACTS. These require runtime consent and allow the app to query the Contacts Provider for entries and fields you store. Android Developers+1 - iOS. Apps use the Contacts framework. The first time an app requests contacts, iOS shows a system prompt. Developers must explain why in the app’s Info.plist (

NSContactsUsageDescription). Without consent, access is blocked. Apple Developer+2Apple Developer+2

Even though platforms gate access with prompts, what happens after you grant permission is governed by the app’s own code and its privacy policy, plus applicable law.

Why Apps Ask for Contacts (Legit Use Cases vs. Overreach)

Common legitimate purposes

- “Find friends” / invite features (matching your address book to existing users). Many messaging apps do this. WhatsApp, for example, says it uses your contacts to help discover which of your contacts are on the service and to support groups/community features. faq.whatsapp.com

- Contact-based messaging/telephony (e.g., selecting a recipient, showing names instead of numbers). Platform docs are built around these use cases. Apple Developer

Privacy-preserving variants

- Some services hash or otherwise transform phone numbers for contact discovery, or use cryptographic “private set intersection” so the server learns as little as possible beyond matches. Signal has documented enclave- and PSI-based approaches; research describes PSI as computing the intersection of your contacts with the service’s users without exposing the full lists. Signal Messenger+2Signal Messenger+2

- WhatsApp states it creates a hash for non-user contacts and deletes the raw number for those not on WhatsApp. (Hashing is not foolproof privacy, but it’s better than plaintext storage.) faq.whatsapp.com

Overreach or risky patterns

- Uploading the entire address book to company servers for profiling, growth marketing, or to build social graphs—including data about people who never consented or don’t use the app. Historical enforcement actions show this has happened. Federal Trade Commission

- Combining contact data with other data for advertising/targeting or sharing broadly with third parties without clear, specific disclosures. (Regulators have penalized firms for mismatches between claims and practice.) Federal Trade Commission+1

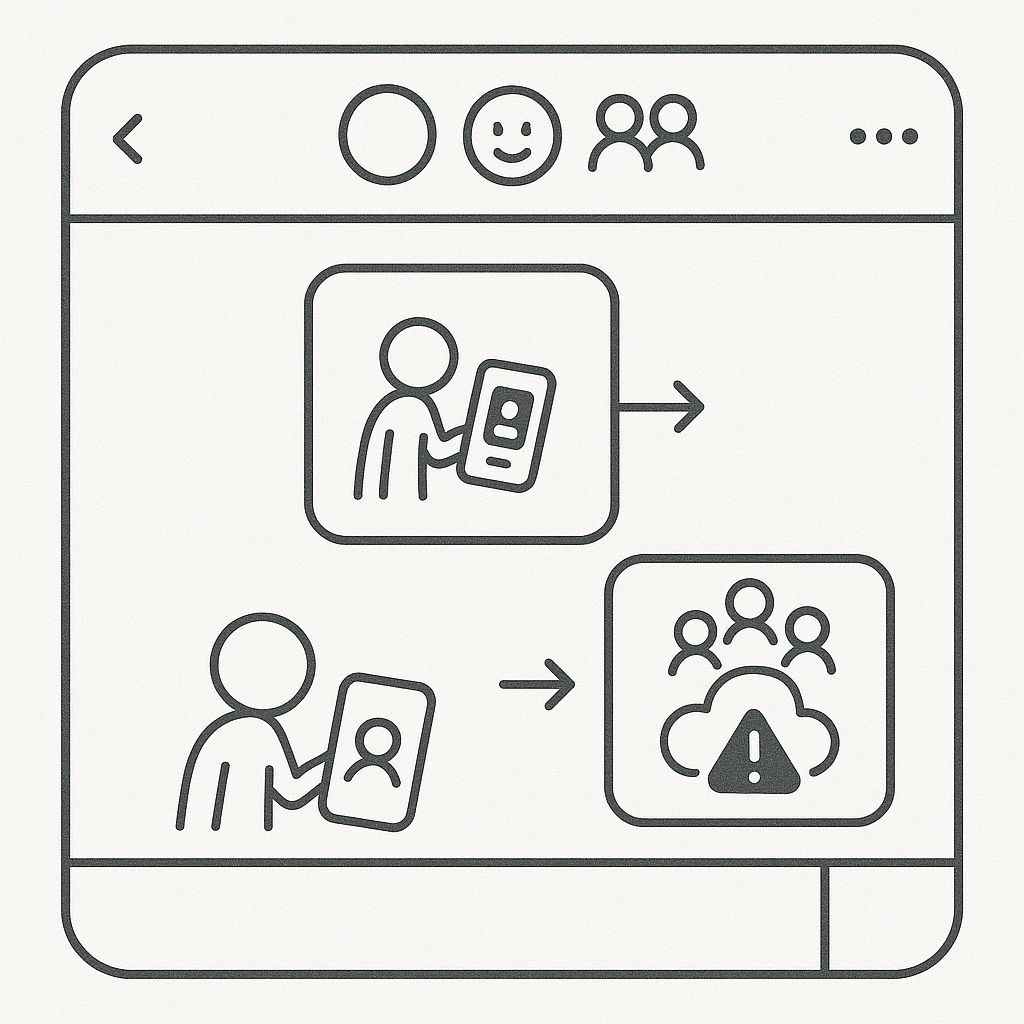

How Contact Data Typically Flows

- On-device access after you tap “Allow.”

- Optional client-side processing (e.g., hash/normalize numbers). faq.whatsapp.com

- Upload to a server (if the product uses server-side matching, spam prevention, backup, or analytics). Signal Messenger

- Storage & sharing internally with the company’s systems and vendors (cloud providers, analytics, anti-abuse services). Whether and how this happens should be disclosed in the privacy policy and app-store “nutrition”/“data safety” labels. Apple Developer+1

- External sharing (e.g., with advertisers, data partners, or “service providers” under U.S. laws). This is where policies matter most: you’re looking for whether contact data (raw or hashed) is “shared,” “sold,” or used for “targeted advertising” or “profiling.” Yes on Prop 24+1

What Policies and App-Store Disclosures Must Say

- Apple App Store requires “App Privacy Details” that state what data types (including Contacts) are collected, the purposes (e.g., app functionality, analytics, advertising), whether the data is linked to you, and whether it’s used to track you. Apple also publicizes “privacy nutrition labels” for its own apps to set expectations. Apple Developer+1

- Google Play requires a “Data safety” section indicating what’s collected, shared, and why (e.g., app functionality vs. advertising), plus security practices. Note: Mozilla found inconsistencies between some Play labels and privacy policies—so labels are helpful but not sufficient. Always read the full policy. Google Help+2Google Help+2

The Law: Why Contacts Count as Personal Data

- GDPR (EU/UK) defines personal data broadly to include any information related to an identifiable person (names, numbers, emails). If an app processes your contacts (including those of third parties in your address book), GDPR applies. Lawful bases can include consent or legitimate interests, but controllers must minimize data, be transparent, and respect rights (access, deletion, etc.). GDPR+1

- California CCPA/CPRA (U.S.) define personal information broadly and create rights to know, delete, and opt out of sale or sharing. If an app “sells” or “shares” contact data (even hashed) for cross-context behavioral advertising, it must disclose and honor opt-outs. California DOJ Attorney General+1

- Enforcement matters. The FTC has pursued firms that uploaded or mishandled address books without proper notice/consent (e.g., the Path app settlement) and has imposed sweeping privacy orders on companies with deceptive practices (Facebook). These cases underscore that contact uploads are sensitive and regulated. Federal Trade Commission+1

Lessons from Real-World Incidents

- Path (2013): Collected address books without knowledge/consent; settled with the FTC, paid a civil penalty, and agreed to long-term privacy audits. Federal Trade Commission

- Facebook (2019): A redesign led to 1.5M users’ email contacts being uploaded during signup without consent; Facebook said it was unintentional and deleted the data. Paired with broader FTC actions against Facebook, this shows regulators focus on mismatches between practice and promises. Business Insider+2Axios+2

How to Read a Privacy Policy for Contact Access (A Field Guide)

When an app requests contacts, jump to sections like “Information We Collect,” “Data Sources,” “How We Use Information,” “Sharing,” “Your Choices,” and “Data Retention.” Scan for:

- Data type clarity. Do they say “we access your address book” (contacts), and which fields (names, numbers, emails, notes, birthdays)? Or do they use vague terms like “may collect information from your device”? Look for specifics. (Apple/Google require specificity in their disclosure forms.) Apple Developer+1

- Purpose limitation. “Find friends,” “enable messaging,” “prevent spam,” or “analytics/ads”? Are ads or profiling mentioned anywhere near contacts? If yes, that’s a red flag. Google Help

- On-device vs. server. Do they process contacts locally or upload them? If uploaded, do they say they hash numbers, and how long they retain them? WhatsApp’s public statements reference hashing and non-user deletion—look for similar claims (and supporting technical details) from others. faq.whatsapp.com

- Sharing categories. Do they disclose transfers to service providers only (for strictly necessary processing), or to advertising/marketing partners and data brokers? Under CPRA, “sale” and “sharing” have specific meanings tied to cross-context ads. Yes on Prop 24

- User & third-party rights. Can you opt-out of sale/sharing? Request deletion? How do they respect the rights of people in your address book who are not users? (This is a hard problem under GDPR; sophisticated services describe their minimization steps.) GDPR

- Security & retention. Do they state encryption at rest/in transit, access controls, and limited retention for unmatched contacts? Absence of retention limits is a warning sign. (Play’s Data safety also asks developers about security practices.) Google Help

- Consistency checks. Compare the privacy policy with the App Store label / Play Data safety. Mozilla found gaps between labels and policies for some top apps; inconsistencies merit caution. WIRED

How Data Is Shared (in Practice)

- Service providers/processors (cloud hosting, crash analytics, anti-abuse). If constrained by contract and used only to provide the service, this can be compliant under GDPR/CPRA. FindLaw Codes

- Ad tech & analytics partners. If contact data (raw or hashed) is used or combined for targeted ads or audience matching, that’s typically “sharing” or even “sale” under CPRA, triggering opt-out rights and prominent disclosures. Yes on Prop 24

- Cross-product sharing inside a corporate group. App families sometimes combine metadata for personalization or safety. Apple/Google require disclosure of such uses in labels; policies must accurately reflect internal data flows. Apple Developer+1

Red Flags in Permissions & Policies

- Asking for contacts when the feature set doesn’t need them.

- Vague purposes like “improving our services,” “marketing,” or “partner offers” near the contacts section.

- No mention of hashing, minimization, or retention for non-user contacts.

- Conflicts between the in-store disclosure and the full privacy policy. (Mozilla highlighted this risk in Google Play’s self-reported Data safety.) WIRED

Practical Steps for Users & Teams

For users

- Deny by default. Grant contact access only when the feature clearly requires it. Both iOS and Android support revoking later in Settings. (Permissions are granular and revocable.) Android Developers

- Check store disclosures + policy. Read the Data Safety/App Privacy sections and the site policy—look for matches. Google Help+1

- Prefer privacy-preserving apps for friend-finding (those that document hashing/PSI and minimal retention). Signal’s approach is a clear example of trying to reduce server knowledge. Signal Messenger+1

For product/legal teams

- Minimize. Use on-device matching or PSI where feasible; don’t store unmatched contacts. Document retention. Pet Symposium

- Be specific in notices. Disclose fields collected, purposes, storage, retention, and sharing categories—in the policy and app-store forms. Apple Developer+1

- Align reality with claims. Path/Facebook cases show regulators punish mismatches. Audit code paths and third-party SDKs. Federal Trade Commission+1

- Respect non-user data. Treat address-book entries as personal data with full compliance duties (lawful basis, minimization, security, deletion). GDPR

Bottom Line

“Access to contacts” is not just a convenience toggle; it opens a sensitive data pathway about you and the people who trust you with their numbers and emails. On both Android and iOS, permission prompts control the door—policies and practices determine what happens next. Demand specific, accurate disclosures (App Store/Play labels + privacy policies), look for privacy-preserving matching (hashing/PSI), and treat contact lists as regulated personal data with strict limits on collection, use, sharing, and retention. GDPR+3Apple Developer+3Google Help+3

Selected sources & references: Android permissions overview and contacts APIs; Apple Contacts framework and App Privacy details; Google Play Data safety guidance; GDPR Art. 4; California CCPA/CPRA; FTC actions (Path; Facebook); WhatsApp contact-handling statements; PSI research and Signal’s private contact discovery notes; Mozilla’s analysis of Play labels. WIRED+17Android Developers+17Android Developers+17

Leave a Reply