by Jeremy Abram

“The future will remember everything, and nothing.” — The Archivist, Fragment VII

I. The Paradox of Infinite Memory

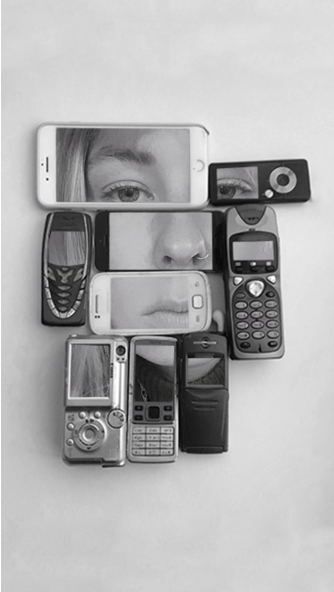

Never before in human history has remembering been so effortless — or so meaningless. Our machines remember for us. Every photo, message, and stray thought finds its way into clouds whose scale rivals myth. The digital realm has become humanity’s great external brain: an infinite archive built to preserve every byte of existence.

And yet, we are forgetting faster than ever.

The paradox of digital memory is that it abolishes forgetting while eroding meaning. In the analog age, memory was an act — selective, interpretive, human. Forgetting was not failure but function: it pruned, shaped, and clarified. Now, with infinite storage, the act of remembering has been outsourced to servers. But what we gain in data, we lose in narrative.

We are surrounded by memory, but starved of remembrance.

II. The Ephemeral Empire

Scroll, refresh, swipe — our rituals of the present tense. Social media, once hailed as the new diary, now resembles an eternal now. Each post is a flare, bright and brief, swallowed by the algorithmic churn. Ephemerality has become the texture of digital life: designed obsolescence of meaning.

Platforms like Snapchat or Threads understand something profound — and unsettling — about our psychology. In a world of infinite archives, the only scarcity is attention. Ephemerality becomes rebellion. Forgetting becomes a feature.

Yet this is not true forgetting. It’s deletion without decay, absence without loss. The content vanishes, but the metadata remains — the ghost of a life still indexed, stored, monetized. Our digital oblivion is not emptiness but excess.

III. The Archive as Abyss

The dream of the archive — of total preservation — once promised salvation. The Library of Alexandria reborn in silicon. The cloud as a cathedral of collective memory. But we may have mistaken accumulation for remembrance.

Every archive, physical or digital, depends on curation. Without hierarchy or interpretation, data devolves into noise. Infinite storage gives us the illusion of eternal memory while collapsing context. The more we store, the less we recall.

This is the age of archival amnesia — the inability to find meaning in what we have preserved.

What does it mean to “remember” in a world where every memory is instantly retrievable but rarely revisited? We no longer forget facts; we forget how to care.

IV. The Right to Forget

Amid this crisis of overmemory, a counterforce emerges: the right to be forgotten. A legal, ethical, almost existential demand to erase — to reclaim the dignity of oblivion. In Europe’s digital charters, in activists’ calls to delete biometric data, in the quiet human urge to move on — forgetting has become a right.

The tension between digital immortality and digital erasure defines our era. Should the past persist unaltered, or be allowed to fade? Should our data live longer than we do? In the age of algorithmic resurrection — when an AI can reconstruct your voice from fragments, your likeness from pixels — death itself becomes a data problem.

The question is not only who remembers us, but who owns our memory.

V. Building Tomorrow’s Memory

Perhaps the future archive will not be a warehouse of data, but a choreography of meaning. The task is not to store more, but to remember better — to design systems that privilege story over volume, essence over exhaust.

Digital memory must learn from its biological ancestor: remembering not everything, but what matters.

This requires a cultural shift. Designers, technologists, and artists must think archivally, not archivistically — shaping digital culture around interpretation, not hoarding. The “cloud” should become less a dump of existence than a conversation with the future.

In the Age of Creation, memory was liberation — the act of building continuity across time. In our current age, creation itself depends on discernment: knowing what to keep, and what to let go.

VI. The Oblivion We Choose

We may yet discover that forgetting is not the enemy of memory but its guardian. Every act of deletion is an act of design. Every absence, a form of care.

If we are indeed building tomorrow’s archive, we must build it with humility — knowing that some things are meant to vanish. The task of the future archivist is not to hoard the past, but to curate the void.

To remember well, we must forget well.

Otherwise, tomorrow’s archive will be nothing but a beautifully organized oblivion.

Leave a Reply