How Personal Digital Device Use Reshaped Work Performance — From Pagers to Smartphones

Want a clear, personal baseline? I built a short Digital Device Dependency Assessment you can take in a few minutes to measure how often digital device habits are fragmenting your focus at work (office, field, or remote). It’s not a diagnosis tool — it’s a practical mirror: a score you can print/save, revisit over time, and use to guide realistic boundary changes that protect performance, credibility, and calm. Take the Digital Device Dependency Assessment here.

I. Introduction: The Invisible Cost Structure of Attention

In less than 30 years, the workplace transitioned from landlines and fax machines to smartphones, instant messaging platforms, wearable devices, and AI-powered assistants. What began as tools for connectivity have evolved into persistent attention competitors.

For employers reviewing this for policy, training, or strategic planning, the central question is not:

“Are phones distracting?”

It is:

What measurable productivity, safety, cognitive, and financial impacts occur when digital device usage is unmonitored or unmanaged?

This article examines:

- Historical productivity data before mobile digital saturation

- Research on interruption science and cognitive switching

- Field, office, and remote-work case studies

- Measurable financial impact estimates

- Abuse patterns and workarounds

- Legal mitigation strategies for employers

This analysis aligns with broader themes of technological friction, systemic tradeoffs, and hidden cost externalities — the same structural lens often explored in JeremyAbram.net’s technology essays.

II. Historical Baseline: Productivity Before the Always-On Era

A. Pre-Digital (Pre-1995)

Workplace structure before mass mobile adoption included:

- Fixed-location communication (landline telephones)

- Written memos and physical documentation

- Limited after-hours accessibility

- No push notifications

- No algorithmic feeds

Productivity measurement during this period focused on:

- Units produced per hour (manufacturing)

- Billable hours (professional services)

- Typing and clerical throughput

- In-person supervisory observation

Interruption frequency was largely environmental and visible.

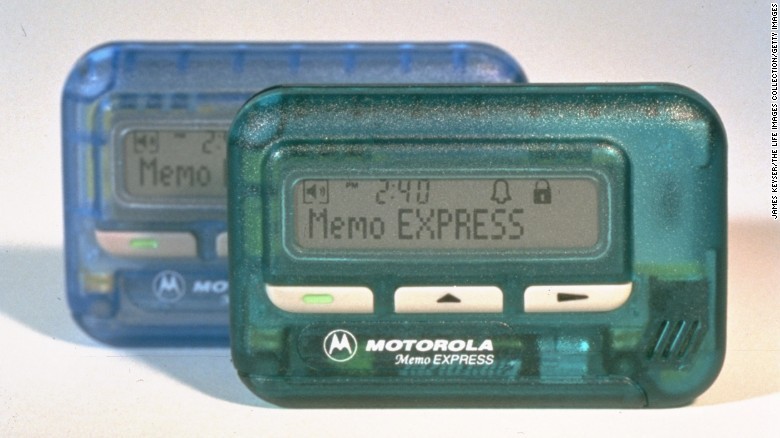

B. Pager Era (Late 1980s–Early 2000s)

Pagers introduced:

- Asynchronous alerts

- Delayed response expectation

- Limited message content (numeric codes)

Importantly:

- Pagers did not offer entertainment.

- They did not provide scrolling feeds.

- They required a separate phone to respond.

Impact on productivity:

Interruption existed, but content depth was minimal. Cognitive diversion was short-lived.

C. Early Mobile Phones (2000–2007)

The BlackBerry era introduced:

- Email in pocket

- Limited SMS

- Basic web access

Work productivity initially improved in managerial and sales sectors due to real-time communication.

However:

- After-hours work expectations increased.

- Boundary erosion began.

D. Smartphone Era (2007–Present)

The launch of the iPhone (2007) marked a behavioral shift:

- Always-on internet

- Social media ecosystems

- Push notifications

- Algorithmically optimized attention loops

- Entertainment, shopping, gambling, and streaming in-pocket

This is where the productivity question becomes measurable and complex.

III. The Cognitive Science of Interruption

Research in cognitive psychology consistently shows:

1. Task Switching Costs

- Studies from the University of California, Irvine (Gloria Mark et al.) demonstrate:

- Average interruption recovery time: ~23 minutes

- Frequent task switching reduces deep work capacity

- American Psychological Association research indicates:

- Switching tasks can reduce productivity by up to 40%

2. Micro-Distractions vs Deep Work

Even brief glances at phones:

- Increase cognitive residue

- Fragment working memory

- Reduce analytical depth

Neuroscience research suggests:

- Dopamine-reward feedback loops reinforce compulsive checking

- Anticipation of notification reduces focus even without active checking

Key finding:

The mere presence of a smartphone in view can reduce available cognitive capacity (Ward et al., 2017, Journal of the Association for Consumer Research).

IV. Quantifying Workplace Impact by Sector

A. Office & Knowledge Work

Common Patterns:

- Social media scrolling

- Messaging apps

- Personal email

- News feeds

- Online shopping

Estimated Productivity Loss:

- Various corporate analyses estimate 1–3 hours/day lost to non-work phone usage.

- If a $30/hour employee loses 1 hour/day:

- $30/day

- ~$7,500/year per employee (250 workdays)

For a 100-employee company:

- ~$750,000/year potential productivity leakage

These are conservative estimates and do not include:

- Error rates

- Rework

- Reduced innovation depth

B. Field Work & Industrial Settings

Risks expand beyond productivity:

- OSHA reports identify distraction as a contributing factor in injuries.

- National Safety Council data shows cell phone distraction linked to:

- Equipment mishandling

- Vehicle incidents

- Reduced situational awareness

Financial impact includes:

- Workers’ compensation claims

- Insurance premium increases

- Litigation exposure

One industrial case study (construction sector) showed:

- 18% drop in minor incident reports after phone restriction policy implemented.

C. Remote Work Environment

Remote work amplifies the challenge:

- Lack of physical supervision

- Blurred home/work boundary

- Multi-device environment (TV, tablet, phone)

Stanford research (Nicholas Bloom et al.) found:

- Productivity depends heavily on self-discipline and monitoring structures.

Digital distraction in remote settings often:

- Extends work hours

- Reduces effective hourly output

- Increases burnout

The paradox:

Employees may work longer — yet produce less focused output per hour.

V. Hidden Economic Externalities

A. Consumer Price Inflation

When productivity drops:

- Companies absorb cost

- Or pass cost to consumer

If productivity decreases 5–10% across sectors:

- Output per labor dollar declines

- Prices adjust upward

This hidden cost of distraction:

- Is distributed across entire markets

- Rarely attributed directly to digital device misuse

B. Insurance and Liability Costs

Distracted employees:

- Increase accident probability

- Increase compliance violations

- Increase HR investigations

This translates into:

- Higher premiums

- Legal defense costs

- Settlement payouts

VI. Abuse Methods & Common Workarounds

For employers reviewing risk:

Common concealment patterns include:

- Phone under desk usage

- Smartwatch notification scanning

- Bathroom break extension scrolling

- Bluetooth earbuds disguised as compliance devices

- “Research” browser tabs masking entertainment

- Secondary device (personal phone alongside company device)

- Remote workers using mouse-mover software

These behaviors:

- Are often normalized culturally

- Escalate when boundaries are unclear

VII. Legal Mitigation Strategies for Employers

Employers must balance:

- Productivity protection

- Employee morale

- Legal compliance

- Privacy law

1. Clear Policy Drafting

Policies should:

- Define acceptable use

- Clarify break-time allowances

- State monitoring practices

- Include safety rationale

2. Monitoring (Where Legal)

Options:

- Network-level monitoring

- Device management software

- Restricted WiFi segmentation

- Geofencing in industrial settings

Employers must comply with:

- State privacy laws

- Federal labor regulations

- Notice requirements

3. Behavioral Interventions

Research shows:

- Total bans often fail culturally.

- Structured usage windows perform better.

Examples:

- Device lockers in manufacturing

- Scheduled personal device check breaks

- Phone-free meetings

- Incentivized productivity blocks

4. Environmental Redesign

- Reducing notification culture

- Encouraging deep work sessions

- Restructuring performance metrics around output, not presence

VIII. The Ethical Complexity

Digital devices are not purely negative:

They:

- Increase responsiveness

- Improve emergency communication

- Enable remote flexibility

- Support family coordination

The issue is unmanaged use.

The system-level insight:

The tool designed for connection became a competitor for human attention.

IX. Global Economic Scope

If we conservatively estimate:

- 1 hour/day lost globally

- 1 billion knowledge workers affected

- Average wage $20/hour globally

Daily productivity loss:

$20 billion/day

Annualized (250 workdays):

$5 trillion+

Even if overestimated by 50%, the macroeconomic impact remains staggering.

X. The Prelude to a Larger Examination

This article establishes:

- The cognitive science foundation

- The historical transition

- The economic implications

- The abuse mechanisms

- The mitigation frameworks

A full-length book could expand into:

- Industry-specific breakdowns

- Legal case law analysis

- Insurance modeling

- Behavioral addiction science

- Cultural normalization studies

- International regulatory comparisons

- Consumer price impact modeling

- Technology design ethics

- Corporate surveillance risks

Final Reflection

The question is not whether phones reduce productivity.

The question is:

How much, in what contexts, and at what systemic cost?

For employers, ignoring the issue may mean:

- Silent revenue erosion

- Increased liability

- Cultural decay of focus

For employees, unmanaged use may mean:

- Reduced career growth

- Cognitive fragmentation

- Long-term professional stagnation

For society:

It may mean we are unknowingly pricing distraction into everything we buy.

Want a clear, personal baseline? I built a short Digital Device Dependency Assessment you can take in a few minutes to measure how often digital device habits are fragmenting your focus at work (office, field, or remote). It’s not a diagnosis tool — it’s a practical mirror: a score you can print/save, revisit over time, and use to guide realistic boundary changes that protect performance, credibility, and calm. Take the Digital Device Dependency Assessment here.